TL:DR - A dramatic drop in maths achievement levels was announced last year via the Curriculum Insights and Progress Study, and a lifting of expectations signalled in the new maths curriculum. However, when some testing comparison tables were released this week…expectations are in fact the same as they have always been.

This week, the Ministry of Education released some long awaited assessment and reporting information, including e-asTTle conversion tables, showing how students’ current assessment scores align with the refreshed curriculum, Te Mātaiaho. After months of headlines highlighting a steep drop in achievement, the tables revealed something weirdly reassuring: the expectations for learners have remained much the same, and potentially lower in some places. It reminded me of the famous song by The Who, The Kids Are Alright - and indeed, despite all the political noise, our kids are largely alright. And perhaps, they always were.

Two caveats here: yes, we need to address underachievement and equity in our country’s education system, and yes I know…the e-asTTle conversion tables are just about ‘one test, on one day’ - but I would argue that the messaging around all of this is the real conversation to be had.

How did we get here?

In 2024, the political and media narrative around education was unmistakably grim. Previously the 2022 National Monitoring Study of Student Achievement (NMSSA) in maths showed only 42 percent of Year 8 students were at the level they should be by the time they start secondary school, with 82 percent of Year 4 students being at an expected level. In August 2024 Prime Minister Christopher Luxon warned that only 22% of Year 8 students were meeting maths expectations using data from the new NMSSA replacement, the Curriculum Insights and Progress Study. "We have a real crisis," Luxon said. The new curriculum benchmarking indicated that a smaller proportion of students were meeting the Year 8 expectation for the draft curriculum statement compared with the previous 2007 curriculum (22 percent against the new compared with 42 percent against the old). This figure was 28% at Year 6, and 20% at Year 3…a contrast to the Year 4 82% figure in the 2022 NMSSA study. This is a 20% drop for Year 8, and approximately 60% for Year 4…children that were doing alright, would no longer be measured as doing alright against our new curriculum it would seem. So, the message to the sector and our communities was clear…our kids are not alright.

This new data led to a new maths curriculum being implemented a year earlier than expected, to deal with this ‘crisis’. Education Minister Erica Stanford stated, “Every single year, 60,000 new kids start school, and we have to start them off on the right track”.

Schools across the country took these messages to heart. We invested in professional development, reviewed assessment practices, and prepared families for what we were led to believe would be a confronting new picture of student achievement. We were told to prepare for a sharp decline in reported outcomes under the new system.

The New Conversion Tables: A Reality Check

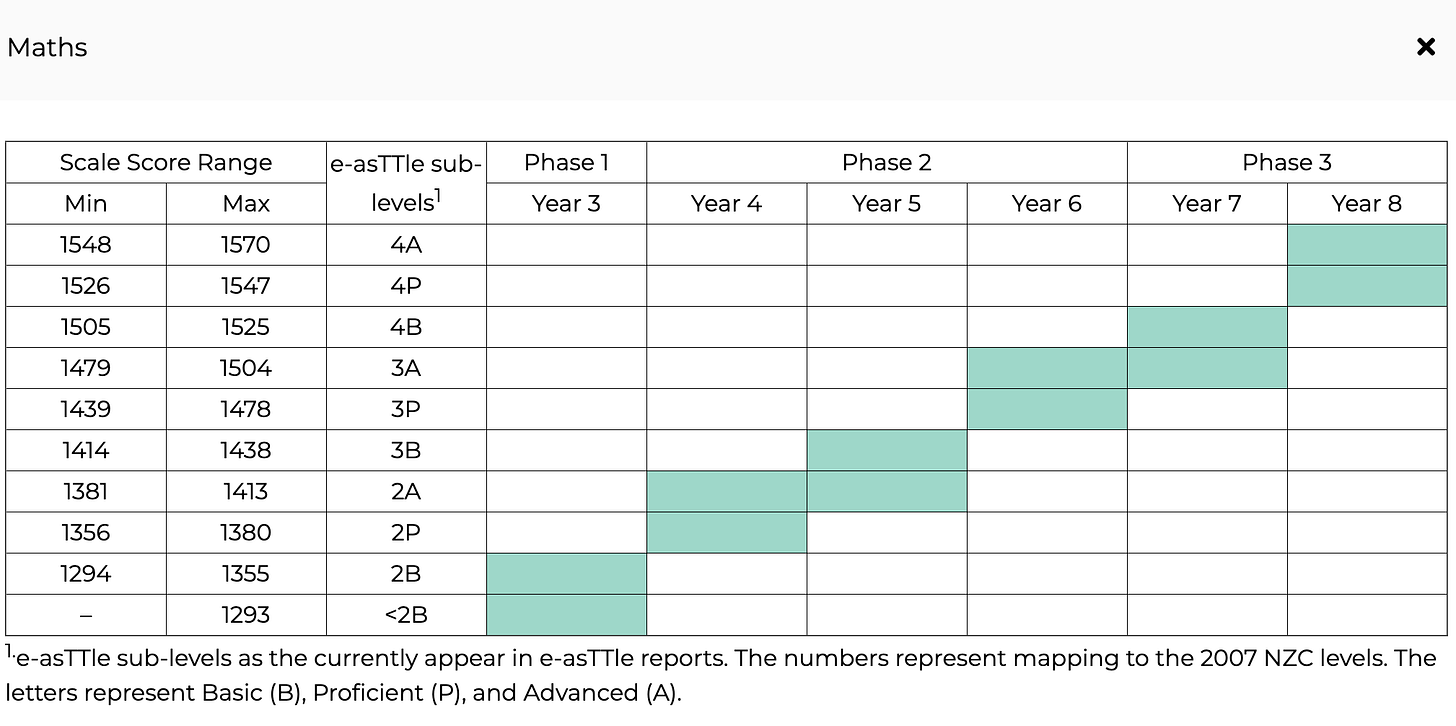

But when the e-asTTle conversion tables were finally released, they told a very different story. Instead of a dramatic lifting in the expectations against the new refreshed curriculum, they showed that students performing well under e-asTTle last year — for example, Year 8’s at levels like 4P or 4A — would still meet expectations under Te Mātaiaho.

This doesn’t magically mean our students are now performing higher (children who don’t perform well in e-asTTle could still expect to be measured poorly against the new curriculum), but when you align this with the fact that we have been tracking student achievement in mathematics at Year 8 for more than 10 years, and in that time, there has been no evidence for improvement or decline…was last year really a crisis point? Surely if the new curriculum was a lift in expectations to raise overall achievement levels, then the testing expectations in a tool like easttle would also need to be lifted?

That drop in measured achievement (a 20% drop for Year 8, and an approximate 60% drop for Year 4) must mean that a child achieving alright in e-asTTle previously (a Year 8 testing at 4P for example) would no longer be doing well…but that doesn’t appear to be case in the Ministry’s new conversion tables.

The feared collapse in achievement rates doesn’t seem founded - the reality being presented here is that children who were ‘doing fine’ against previous expectations, are still doing fine. The Kids Are Alright - in fact, when looking at the conversion table it could be argued that some of the expectations are lower, Years 3 and 5 in particular.

The gap between the crisis messaging and the reality on the ground has left many in education feeling uneasy. For some, it’s felt uncomfortably close to gaslighting — being told that things are in disastrous decline, only to find that expectations have stayed largely where they’ve always been. That kind of messaging can erode trust and damage morale.

Implications for Schools and Learners

For schools, the consequences are real. Teachers braced for a tidal wave of underachievement. Families were prepared to hear that their children were falling short. Now, we’re left to untangle the mixed signals: should we still act as if we’re in crisis mode, or was the crisis overstated from the start? Either way, the emotional and professional cost of this mismatch should not be underestimated. It is hard hearing that the kids aren’t alright, that the system had let them down, that classroom practice wasn’t effective…only to see that in fact the kids are alright.

What Schools Will Focus On Anyway

Regardless of the political noise, schools remain focused on what matters: helping every child succeed. We will continue setting high academic expectations, delivering strong teaching, engaging with whānau, and nurturing wellbeing. We know improvement comes not from panic, but from calm, focused, evidence-based practice. And, as the e-asTTle testing data will probably now confirm, many of our kids were doing just fine all along…the kids are alright. The cynic in me is thinking that when achievement results are collected at the end of 2025 or in mid 2026 the shifted goalposts could lead to improved outcomes in an election year…a win for the government, but perhaps not a win based in reality.

Trust arrives on a horse, and leaves in a Ferrari

If the Minister and Ministry want to build genuine momentum for change, it needs to match its rhetoric with reality. Overhyping a crisis that doesn’t fully materialise risks damaging trust and exhausting the very people tasked with improving outcomes. Educational progress is a shared responsibility — but it must be grounded in honesty, not alarm. Because in the end, their own evidence and expectations have caught up with what many educators already knew: the kids are alright.

Thank you, Gareth, for bringing a thoughtful perspective to a conversation that has felt increasingly disconnected from the classroom reality. The latest data highlights what many educators have quietly known — that while we must continue working hard to lift outcomes and address inequity, the dramatic drop in achievement may not have been as clear-cut as first presented. A calm, evidence-based approach is what our learners and teachers need — not alarm, but clarity, consistency, and trust in the work we do every day. Our role hasn’t changed: to support every learner with high expectations, sound practice, and steady leadership.

An interesting and helpful analysis - thank you for taking the time to collect that information and write it up so accessibly. I was certainly expecting a big drop in data as all the students were expected to "catch up" with the new curriculum. Feeling a wee bit duped here!