Bevan Holloway writes the blog ‘Democracy Begins in The Classroom’. Read more from Bevan here: https://bevanholloway.com/

2024 had been a good year for Stanford. The speed bump that was the outcry over the senior English curriculum and the lack of consultation had been smoothly managed by her, and she was on a roll with the ‘Make it Count’ maths plan and the impending rollout of the junior English curriculum. Rata, too, had experienced the kind of year she had long desired, playing a key role on the MAG, then leading the senior English curriculum writing team and putting her curriculum writing framework into use.

But when I close my eyes and think of the days in late October, 2024, I see swirls of elation contrasted with heaves of desperation.

Because, by 28 October, things had turned. While Stanford was on a high at the Consilium conference in Australia, Rata feared she had lost control of the senior English curriculum. That fear was justified. But, with everything she had worked for at risk, Rata did not stand down. Instead, she stayed on message with Stanford and her office: the curriculum needed to be saved.

Her fear turned out to be short-lived. Two draft English curricula dated March 2024 exist. One, approved by the Curriculum Coherence Group, while still a highly structured, knowledge-rich document, contained no Shakespeare and stipulated the inclusion of Māori and Pacifica authors. The other, the version the sector saw and was out for consultation, included Shakespeare and the stipulation around Māori and Pacifica authors had been removed.

Who made those changes?

There is no direct evidence. However, there are a number of things we can look to to help us draw conclusions. One is that Stanford’s term as Minister has been characterised by the continual disregard of public service guidelines as she has pursued the embedding of a knowledge-rich curriculum. Another is that there are key, prominent individuals Stanford has brought into the Ministry’s work who are accustomed to operating in that way. Another is that during a curriculum change process it is usual for a Minister to have all the different versions produced as well as the detail of why the changes were made.

Therefore, it is not out of the realms of possibility that the changes made to the senior English curriculum before it went out for consultation were done in a way that violate the processes in place that are so important in protecting our democratic institutions. Furthermore, it is of significant concern if the changes were done without the knowledge of the Minister – this would be a major departure from usual practice and suggest there are undemocratic forces at work in the Ministry. Even worse, if the changes were made and the Minister was aware, this is a violation of regulatory process so egregious is it hard to see how the Minister can remain in her role.

For we are not just talking about a pedagogical difference of opinion here. A curriculum is secondary legislation – it is the legal document that sets out how the Education and Training Act is realised in a school. Therefore, it must be developed lawfully. If it hasn’t been, those responsible must be held to account for subverting the processes and institutions essential to our democracy. We are all vulnerable, no matter our political position, when that becomes the way things are done.

Early 2024: process violations established as modus operandi

There is no doubt Rata was a key member of the MAG Stanford put together. Keen to make good on the election promise of teaching the basics brilliantly, the MAG was to review the refresh work done over the last three years and “report to the Minister on the English and mathematics and statistics learning areas in the first three phases [ie, up to Year 10]”. However, Rata was never recommended as a member by the Ministry. Her long history of collaboration with the MAG chair, Michael Johnson, no doubt played a role in Stanford bringing her on, a decision which overrode the Ministry’s advice, as did her decision to make Johnson chair.

From the very first email chains it is clear that Rata is keen to get underway with “our work”. But it’s not the work that one expects an advisory group to be doing. There is very little review of the existing curriculum happening. Instead, the group are quickly examining England’s curriculum and finding much in it they like. Rata suggests they “not reinvent the wheel but take the best of what others have done and fit it to our needs”. By 18 January, 2024, she is “writing a piece about the English Literature strand”, which is sent to the MAG on 22 January. It is a short piece “for Michael to use in the piece he’s writing for the Minister” – Johnson’s reply shows it is destined for the MAG’s report. With the terms not including Years 11-13, it is not clear how this is in the MAG’s scope.

This kind of behaviour – disregarding terms, scope, and public service guidelines – is a constant throughout the MAG’s operational time. It surfaces strongly in early February when they are warned by Anya Pollock about doing the work of government (ie, writing curriculum documents), and is apparent in late March. On the 23rd, three days after the MAG submits its report to the Minister, Rata sends Johnson a doc called ‘Subject English Curriculum Writing Team’, which has some “Ideas to get us started when we receive the go-ahead.” Tim O’Connor, Headmaster of Auckland Grammar, is in the loop, having given his approval for two of his teachers to be on the proposed eight-strong writing team. There is clearly a sense of this being a done deal.

But let’s pause here. The MAG’s terms state that once they have submitted their report, “the Minister will decide which of the recommendations to progress further”. From there, it is to be the Ministry that gets to work, with the report’s accepted recommendations being used “to provide direction for the curriculum developers to draft the redesigned curriculum content … The Ministry will check in with the Group as the work is being developed … The Group will provide quality assurance … and make recommendations on implementation supports by June 2024”. Rata is acting in a way that is undercutting those terms here. The Minister has yet to accept their recommendations (she does this on 5 April), so there is no “go-ahead” to be getting ready for. And even when given, it is the work of the Ministry to be organising curriculum writing teams, not Rata, and definitely not Auckland Grammar.

Stanford was aware that the MAG was operating beyond its terms and in violation of public service guidelines. A 15 March, 2024, briefing paper to her detailed the curriculum development the MAG was involved in, working with and directing the Literacy Contributors Group – this is before they submitted their report and well outside the bounds of permitted actions by an advisory group. It may even be possible Stanford gave the green light to them operating in this manner. In a text to Johnson on 22 December, 2023, three days after the official formation of the MAG, she says “You can start the second part of the work when you like”. When the only work for these kinds of groups is to advise, what is the “second part” she has authorised?

May 2024: curriculum development

Rata, despite the reservations of the Ministry’s procurement team – one of whom asked to be put on a different piece of work because “it seemed to be quite difficult to find justification for some of the writers who were proposed to be hired” – eventually was able to start writing the senior English curriculum with her team in early May, holding two writing workshops at Auckland Grammar. It is worth noting that Stanford said in an RNZ interview on 12 June that “The MoE have now gone and put writing groups together which are quite separate from the MAG … they’ve used their own processes … I didn’t even know who the people were until just recently … and they’re now putting together some ideas … they’ve only just started writing”.

However, the veracity of the claim the Ministry is in control here must be challenged. In a meeting Johnson has with senior Ministry officials on 14 March, it is clear the MAG is in the driving seat. An email from Pollock to Johnson the following day makes it clear the advisors have become the implementers. A small group of unelected individuals, none of whom are employed in the Ministry, are directing the work of a government agency, a clear violation of public service guidelines.

Rata’s small team make quick progress, and by 20 May a significant chunk of the curriculum is written. So much for Stanford’s claim they’d only just started writing. Students and teachers could look forward to vocabulary lists, instruction in grammar, Shakespeare studies, and The History of New Zealand English, among other things.

A quality assurance process is put in place, to be managed by ERO: perhaps the number of MAG members who went on to the curriculum writing teams meant having the MAG provide QA was deemed a bridge too far? Rata needs reminding to submit her reports. And ERO’s feedback at the checkpoints clearly irks her – she gives feedback on their feedback, obviously keen to hold her ground. This is understandable. Up until this point, Rata has been able to dictate terms.

Mid 2024: Rata loses control

The QA process is not plain sailing for the senior and junior English curriculum writing teams. ERO refuses to review the first sample sent by the junior writing team:

“these materials were originally written by the Ministerial Advisory Group (MAG) with the purpose of being a sample for the MOE writing group. ERO welcomes the opportunity to QA this again when the writing group has progressed this area and material is more reflective of the most up to date evidence around effective pedagogy, as some of this is currently outdated.”

On 16 August, just prior to the junior curriculum going out for consolation, ERO deems it “not fit for purpose”, with significant sections requiring “critical revision”. In September, the international review panel provide three key messages: greater clarity was needed; “concern about learners from diverse backgrounds was noted in particular when considering pedagogical approaches that can lack an acknowledgement of what learners bring to a classroom”; there was concern about its narrow focus.

While happy to release those unflattering documents to me (eventually: I had to threaten the involvement of the Ombudsman after an almost 6 month delay), ERO have withheld the feedback, and indeed all communications, they provided to Rata and her team regarding the senior English curriculum. One must wonder why. Just how unfit for purpose was the curriculum that Rata’s team developed?

Nevertheless, on 19 October Rata is on a panel with Stanford at the National Party Northern Region Policy Day (Stanford claims in an OIA cover letter received on 8 September, 2025, that she did not know Rata was going to be on the panel). The next morning, Rata emails Stanford with her speech notes from that day and asks for a meeting, which Stanford says never happened. In that speech, Rata attacks the ‘Learning Approach’ – with its open plan classrooms and culturally responsive practice – as part of expounding on the four features and necessity of a knowledge-rich curriculum. It is, she argues, the Learning Approach and the “unholy alliance” it has with decolonisation that has led to the decline in our “once first-class education system”.

But it seems she is aware that her work to date is at risk. And so she issues a call to arms to the National Party attendees: She is unsure “which way the Coalition Government will go” – are we about to “succumb to the easy option of the Learning Approach which by removing academic subjects, opens the way for decolonisation and the political project of retribalisation”, she asks? The very future of New Zealand is at risk. But she is doing what she can to honour the vision of our founders.

“Earlier this year I was privileged to be the Lead Writer for the years 7-13 knowledge rich English curriculum (and yes – Shakespeare and Grammar are there). It will be, I hope, along with still-to- be-written Science and History curricula, the circuit breaker in replacing the Learning Approach and ending decolonisation’s success.”

With the recolonisation project laid bare, it is no wonder that Rata loses control of the curriculum rewrite. On 28 October, while Stanford is on her way back from the Consilium Conference in Australia, where she is on a panel with Nick Gibb titled ‘Can education in Australia be reformed?’, Rata emails her with a summary of her 31 July submission to the Ministry. She is clearly panicked, fearful that her chance at using a curriculum to end decolonisation’s success is gone.

The curriculum must be saved from “others”. It is “we” – Stanford and Rata – who are tasked with that work.

Early 2025: a draft, delayed, redrafted, and recaptured

Rata and Emma Chatterton, Stanford’s Senior Ministerial Advisor, write back and forth in February after Rata shares with her a soon-to-be-published article: ‘Re-imagining the curriculum: A case study of the knowledge turn in New Zealand and Flanders’. “I would be really keen to read it”, Chatterton replies, and they make arrangements to meet and discuss it. This meeting never happened according to Stanford in the OIA response letter of 8 September, 2025.

During this time, the draft senior English curriculum was repeatedly delayed. Of course, rumours circulated as to why. NZATE walking away from the process added to the sense of despair felt in the sector. But eventually, it was approved by the Curriculum Coherence Group to be released for consultation. It landed in my inbox on 1 April. To no-one’s surprise, and just as Rata had promised at the National Party Northern Region Policy Day, Shakespeare and grammar are included. A colleague scanned to document and yelled about the dearth of references to Te Tiriti and limited use of te reo Māori.

The draft meets with Rata’s approval. On 21 April she writes to Stanford to congratulate her on it. The senior English curriculum “is the knowledge-rich curriculum you promised”, she writes: “Your leadership in driving this herculean task deserves to be recognised”. She thanks Stanford “for the opportunity to be one of the twenty contributors to the curriculum, in particular to contribute my expertise in curriculum design”.

This expertise Rata lays out in more detail in her submission on the draft. It was developed using her “scientifically justified Curriculum Design Coherence Model (CDC Model)” and, never one to miss an opportunity to cement her legacy, makes a recommendation that “the internal workings of the CDC Model be shown so that it is clear exactly how coherence is achieved through the logical relationships established between concepts and content”. Then, making a clear connection to her speech at the National Party Northern Region Policy Day, she writes that “the Draft excludes the failed ‘learnification’ methods of the 2007 Curriculum”. It is clear she is wanting to establish herself as a key architect of the draft curriculum, despite losing control of it in October. And just as clearly, Rata views this draft curriculum, with its abandonment of the Learning Approach, as a vehicle that will end decolonisation’s success and help recapture the vision of New Zealand’s founders.

But the draft out for consultation, the one she is congratulating Stanford on for her leadership in helping to bring forth, is not the draft approved for consultation by the Curriculum Coherence Group.

March 2025: the two drafts

The differences are small, yet significant, and they start from almost the first page.

Rata has very firm views, views which are encapsulated in her CDC Model which was used to develop the curriculum. That model emphasises the integration of a subject’s concepts, content, and competencies. It derides a focus on emotions and identity. Instead, it emphasises logic under the assumption that being forced to think logically will lead to students developing reason. It is this “knowledge-mind connection that creates understanding and critical thinking”, she tells the National Party audience that day in October, and it is this that is “intelligence. Socio-cultural knowledge doesn’t require this logical response to knowledge”. We are in the state we are in, she argues that day, because we have the embraced the Learning Approach, which has students do things like “Respond to a novel using one’s personal feelings towards the characters and relate to one’s own life”.

I think these give us fingerprints we can look for beyond the headlines of the mandating of Shakespeare and the the removal of the stipulation to include Māori and Pacifica authors to help us think about who made the changes. We must also bear in mind that even though Rata lost control, she was one of 20 writers and she tells us her CDC Model was used to develop it, so what we have is something that will reflect strongly her ideas, even in its signed-off version.

For instance, on page 6, which outlines the key understandings the curriculum seeks to develop, the version signed off by the Coherence Group has this as its second aim:

Language and literature give us insights into ourselves and others. | Mā ō tātou reo me ngā tātai kōrero ka mārama tātou ki a tātou anō, ki tangata kē anō hoki.

Literature and other texts help us to learn more about ourselves, others, and the world around us. As authors, we gradually develop our own voice and identity and make our own unique contributions. This enables us to further understand who we are and helps others to better understand us.

But the version released to the sector for consultation reads:

Language and literature give us insights into the rich diversity of human experiences and imagination. | Kei roto i te reo me ngā momo tuhinga he māramatanga mō te kanorau haumako o ngā wheako ā-tangata me tōna pohewatanga.

Literature and other texts expand our horizons and help us to understand more about ourselves, others, and the world around us. As authors, we gradually develop our own voice and make our own unique contributions.

And so the potential for a personal, subjective response to literature is minimised and turned towards analysis and logic.

For instance, on page 9, the signed off version says this:

In each phase of the curriculum, students build on their knowledge and practices through reading and creating more complex texts. Teachers use their professional judgment, along with clear guidance about what to teach and how to teach it, in response to the prior knowledge, strengths, and experiences that students bring to their learning.

But the released version includes the importance Rata, and Stanford, place on standardisation (bolding mine):

In each phase of the curriculum, students build on their knowledge and practices through reading and creating more complex texts. In response to the prior knowledge, strengths, and experiences that students bring to their learning, teachers deliver tailored learning programmes, drawing on their professional judgment and clear guidance about what to teach and how to teach it.

The reference to tailored learning programmes mirrors the language we find in section 127 of the Education and Training Act amendment, where local curriculum is replaced by that phrase. The Ministry’s advice was that local curriculum was how schools met their obligations to te Tiriti, but Stanford wanted to make the change so schools were forced to be more faithful to the national curriculum. Teaching and learning programmes was the phrase settled on to drive that shift.

For instance, on page 13, the signed off version says this (bolding mine):

Students develop confidence as communicators, readers, and writers by recognising and valuing the use of literacy and English in their lives. This is enhanced when they explore texts that reflect their identities, cultures, interests, and preferences, and especially when they make choices about what they read and write. Developing as confident communicators, readers, and writers also involves creativity in exploring ideas in texts and in crafting and sharing texts.

But the released version removes the reference to the social dimension of learning that “sharing texts” implies, which reflects the importance Rata places on the necessity of curriculum to “individualise the child for future citizenship”:

Students develop confidence as communicators, readers, and writers by recognising and valuing the use of literacy and English in their lives. This is enhanced when they explore texts that reflect their identities, cultures, interests, and preferences, and especially when they make choices about what they read and write. Developing as confident communicators, readers, and writers also involves creativity and imagination.

For instance, on page 14, the signed off version says this (bolding mine):

It is important to include texts that provide windows into different places, times, and cultures (e.g., prose, poetry, plays, novels, contemporary and historical texts, stories from New Zealand, the Pacific, and around the world). Making meaning of these texts provides opportunities to strengthen students’ knowledge and understanding of the world, including Aotearoa New Zealand perspectives.

But the released version removes the word perspectives, which stops our logic from stepping into considering multiple viewpoints of who we are as a nation, and leaves open the potential for the idea of this place to be anchored in a dominant one: students are to understand Aotearoa New Zealand, not Aotearoa New Zealand perspectives. Remove perspectives, and you reduce the potential for the persistence of the Learning Approach, where, Rata says, “Learning activities are to affirm children’s racial identity using ‘culturally responsive pedagogies’”.

And then on page 21 we have the text requirements for Phase 3. In the version signed off, Māori and Pacific authors are included as a must.

But in the version out for consultation, Māori and Pacific authors are erased. This is repeated on page 47 for Phase 4 texts.

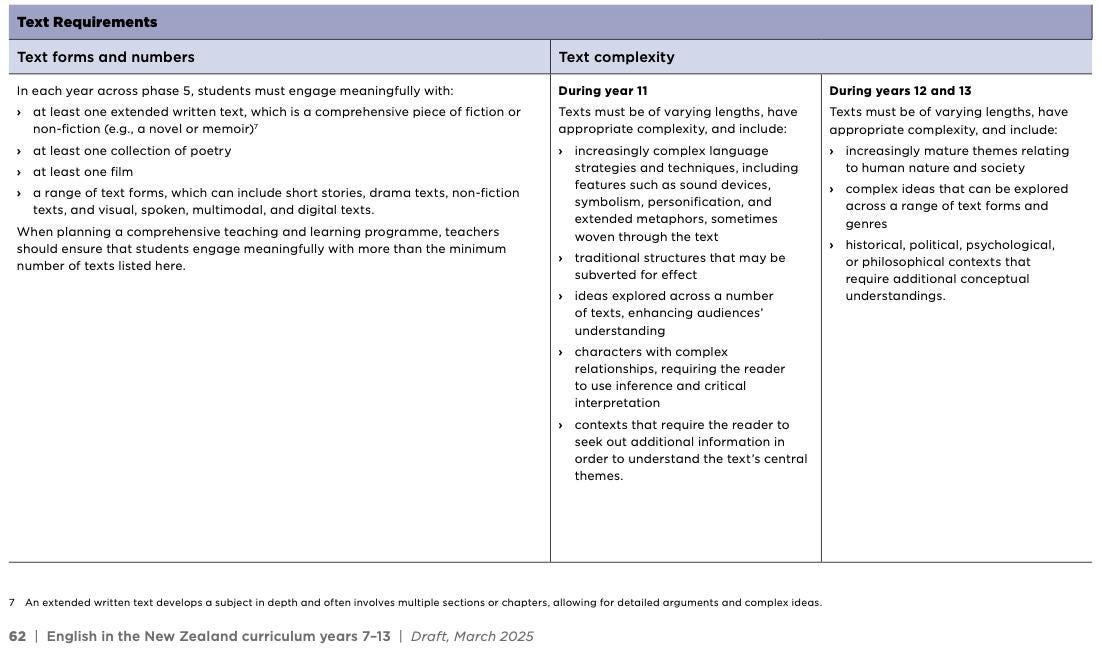

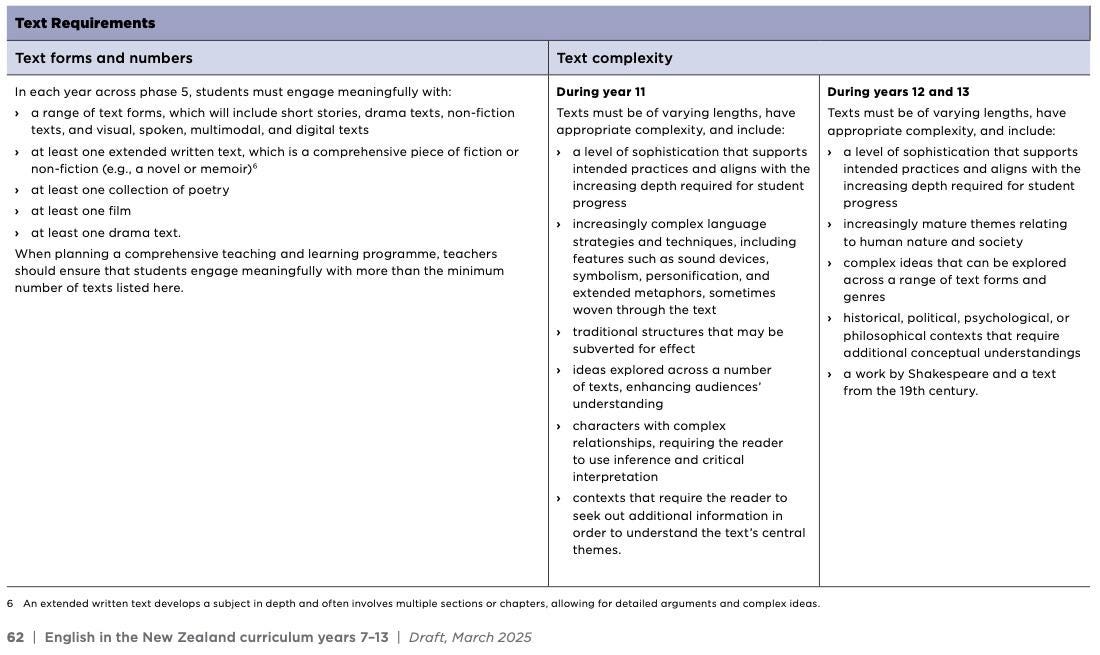

And then on page 62 we have the text requirements for Phase 5. It is here we see Shakespeare.

This is the signed off version, the version where perspectives are allowed, and here teachers must include Māori and Pacific authors. It makes sense: this will support the exploration of the multiple ways of thinking about this place. While Shakespeare is not in the must list, there is nothing here that would stop a teacher teaching any of his works.

This version the sector was asked to consult on. This is the version that removed the word perspectives. Gone is the stipulation teachers must include Māori and Pacific authors. But Shakespeare is a must – teachers have no discretion here, aside from the text of his they choose to teach.

Note, also, the teaching of a text from the 19th century, absent from the signed -off version, is now a must. In Rata’s view, it is the 19th century that is the origin of our prosperous society. It is subject English that plays a key role in connecting students to that lineage:

“Subject English has a very particular role – that of creating society’s cultural repertoire. When we study English at school we are taught, or should be taught, the content and conventions of our nation’s language. New Zealand’s institutions, social practices and values were developed in English. It is the language of the 19th century colonial era and of 20th century nation building. The most effective way to decolonise the nation is by removing English ‘that dangerous language of the eurocentric coloniser’ from the school curriculum”.

And so, ‘perspectives’ and Māori and Pacific authors are erased. Shakespeare and the 19th century are re-centred. The curriculum is a re-colonising tool, just as Rata desired.

Who made the changes to the version signed off by the Curriculum Coherence Group? Why were they made? Did the Minister (or her office) make the changes? Did the Minister (or her office) know about the changes?

Why does this matter?

We are a democratic nation, and democracy is more than elections. It is elections, plus process and guidelines and policy, which work together to ensure we all have a say and a secure place here. In other words, democracy is a partnership. Every three years, we grant a select group the privilege of working with and representing the multiple perspectives in this place, and so govern in a way that does its best to balance those views and interests. While that is, in some ways, an ideal that will never be fully realised, one of the great developments in our democracy over the last 50 years has been the move to decolonise this place, which has meant embracing diverse perspectives and purposefully including Māori and Pacific peoples in the democratic process. Decolonisation has been a process of enfranchisement.

That widening of the ‘democratic lens’ has benefitted all of us.

But what we have seen happen in education, which this curriculum document is an artefact of, is a narrowing of the democratic lens. It literally erases Māori and Pacific authors and the perspectives they bring. It literally replaces them with texts strongly tied to our colonial foundation: Shakespeare, 19th century texts. To achieve this, a small, select group have been able to override the processes and guidelines and policies that act as democratic guardrails within government agencies, and in doing so embed a curriculum that is reflective of a particular idea of what education is and is for. It appears that an even smaller group has been able to edit that curriculum so it is more strongly reflective of that view. It is important to state that that idea is not one that is settled in science, and is not settled from an ethical or values perspective. It is an idea that finds particular currency among groups on the far right who advocate for a unilateral world where they are great again – the coloniser’s mindset, writ anew.

None of us are safe in that world. But that world is possible, even here. It becomes possible slowly, through the erosion of mundane democratic processes and guidelines and policies, until all of a sudden the state becomes a vehicle for the expression of the desires of a small group. As Professors Levitsky and Ziblatt remind us, in moments like these we are faced with a choice: are we semi-loyal actors, only defending democracy if it suits our team, otherwise happy to take the wins no matter how they come; or are we loyal to democracy as an ideal, regardless of who is ‘winning’, willing to defend the importance of those processes and guidelines and policies? One cannot be both. But Levitsky and Ziblatt are clear that semi-loyal actors help lay the path towards democratic backsliding and authoritarianism.

And so, really, this is not about pedagogy. It is about a choice we must make about how we want power to operate in this country. If there is one thing history teaches us, in places where power rests in the hands of the few, that few is smaller than you think.

Don’t bet your kids’ future on them being one of them.

A brilliant forensic investigation into the supine body of home-grown, child-centred bicultural education in Aotearoa. Here's a slogan: "The rata does not always kill the tree."

Thanks for drilling down with this fine grained analysis. Appreciated and really valuable. While I can see that being more explicit about knowledge in a curriculum may well provide a level of clarity for teachers, it is seriously disappointing to see how the idea of 'knowledge rich' is currently being interpreted. There does not appear to be a commitment to genuine consultation or a willingness to consider a wide range of alternative perspectives (especially from those who have expertise in curriculum and who understand the intense pressure our teachers are under). I am not unfamiliar with how the knowledge-rich curriculum has been rolled out in the UK but what seems to be an uncritical and wholehearted attempt to simply transfer these ideas to a NZ context- especially in regards the content to be taught - is really not a good fit. I worry that without a well-thought through and considered consultation process this curriculum initiative is not going to end well. I totally get how consultation can be frustratingly cumbersome and slow things down but ultimately it is a fundamental part of the process and getting things right.