By their objectives ye shall know them: Part 2

By their objectives ye shall know them: Part 2

Terry Locke

If I were to choose a pivotal moment when the potential for teacher deprofessionalisation in the Aotearoa context became pronounced, it would be the publication of the Ministry of Education's Education Gazette (70:7) early in 1991. This was the issue where, under the directive of Lockwood Smith, the newly elected National government announced its "Achievement Initiative". Two of the three main elements of this policy were:

"the establishing of clear achievement standards for all levels of compulsory schooling, first in the basic subjects of English, mathematics, science and technology, and later in other subjects;

"the developing of national assessment procedures at key stages of schooling, by which the learning progress of all students can be monitored in those basic subjects." (Ministry of Education, 1991: 1)

I'll come back to the consequences of this policy later, but first let's revisit some happenings during the tenure in office of the Lange/Douglas regime.

The softening up: 1984–1989

Maybe we should call it the Lange/Douglas/Treasury regime, given the influence of the last of this troika on whom the Government might best ignore in the development of its education policy. A Treasury-driven report on the administrative reforms, published as Today’s Schools, favoured the gradual exclusion of teachers from involvement in central policy-making processes. This was based on the doctrine of "provider capture", which suggested that, as "providers", teachers had far too much say in how teaching should be delivered. ("Delivery" became Newspeak for "teaching" at this time, when it began its meteoric rise in the Aotearoa context. A task force chaired by supermarket entrepreneur Brian Picot, charged with transforming the country’s education system, was entitled Administering for Excellence.)

Key changes resulting from the taskforce recommendations included:

The replacement of the Department of Education with a smaller policy-making ministry;

The dismantling of the old Department of Education’s Curriculum Development Unit and its replacement by a contractual regime for curriculum development;

The abolition of regional education boards;

The devolution of operational responsibilities to individual schools;

The replacement of the old Inspectorate with what we now know as ERO.

The second of these resulted in a purge of expertise across a range of subject areas. As a consequence, the new Ministry put the contract to develop the 1994 English curriculum out for tender and awarded it the Auckland College of Education. (The former Christchurch College of Education had blotted its copybook by developing a draft senior secondary syllabus for English which contained the outrageous suggestion that Māori might be a useful language of comparison with English in Year 13. (If you are interested in this topic, check out Elizabeth Gordon’s wonderful article: “Grammar in New Zealand schools: Two case studies”.)

On the plus side, curriculum reform itself was on the agenda of this government, which had an excellent Minister of Education in Russell Marshall, before he was deposed in favour of Lange. Under Marshall's watch the government undertook a highly consultative Curriculum Review review in 1986 which embedded, among other things, the notion that a more coherent curriculum was needed which would map progressively the desired development of students from Years 1 to 13 in a number of specified domains of learning. A first step towards implementation was made in 1988 with the publication of a draft National Curriculum Statement.

Despite the dominant presence of neo-liberal economic reformers within the Labour Cabinet. the Education Department's 1988 statement was a progressive document which recognised the autonomy of schools and communities, was learner-centred, and focused on such principles as cultural identity, equity, balance and coherence and the need for school programmes to be accountable and responsive to their communities. Its eight 'areas of knowledge' even included 'Culture and Heritage' and 'Creative and Aesthetic Development'! Ironically, its adoption of four broad "bands" of learning to indicate a way of thinking about progression is not dissimilar to what has occurred in the pre-2024 curriculum refresh.

Back to the Achievement Initiative

The 1990s entrenched a separation of policy from implementation which saw broad curriculum development policy established at Ministry level and implementation being conducted by relatively disempowered educational professionals working within pre-set, structural parameters. The Achievement Initiative signalled:

A massive shift from a curriculum oriented to the needs of individual learners to a system describing student learning as measurable against pre-established 'clear objective standards' and state-dictated educational priorities;

A reprioritisation of what became known as the 'Essential Learning Areas' away from the Humanities towards Science and Technology

A reiteration of the notion that assessment is about measuring students against a set of external and predetermined measures of performance, with a concomitant shift away from programme assessment to the assessment of individual learners;

A belief that 'continuity and progression' of learning can be neatly encapsulated in a series of 'key stages' or levels of achievement, describable as a set of 'clear learning outcomes', which would allow for 'sound assessment and monitoring to occur'. Such a belief was the basis for reforms which would redeem the educational system from its past failures by incorporating a transparent method of accountability.

The educational discourse underpinning these bullet points is still powerful, but was being tempered by the pre-2024 refresh writers.

In 1993, the team writing the English curriculum produced a draft which incorporated the structural parameters that they had no input into or control over. (The best they could manage was to have four levels rather than eight for certain "strands".) Input on the draft was managed by the Christchurch-based Duthie Consultancy, which produced a report which even at the time was hard to come by. The report stated clearly that every category of constituency where feedback was sought rejected the validity of the model of progression reflected in the 8-level ladders of AOs (Achievement Objectives). The Duthie findings were subsequently ignored in the mandated 1994 revision.

In 1994, I was HOD English at Pakuranga College. As a department we organised a retreat, where we began the task of re-writing our school English scheme with the new English Curriculum in mind. Within a short time, however, we realised collectively that we could not design a scheme that adopted the EC's model, especially in respect of progression. So were came up with a scheme that accorded with our own knowledge of our students, subject English and how it might best be taught. I made it clear to ERO what we were doing; at no stage did they object. I described our departmental experience in English in Aotearoa and offered to share our scheme with other departments. Around 100 HODs English wrote to me asking for it; they were having the same issues as we were.

Outcomes and objectives

An outcome is the consequence of something. This essay in part is reflecting on the outcomes resulting from the structure of the 1994 English curriculum and its discursive underpinnings. In the last of those four bullets above, there is reference to "clear learning outcomes". In the Newspeak of the time, this meant a focus on things that were measurable. The focus was almost exclusively on the child. Such a focus could allow for a lack of attention to the causes/conditions contributing to the outcome (unless it was the child's home background, which was too often characterised in deficit terms). It was a way of suppressing the acknowledgement of agency of such things as: the hidden curriculum, the nature of the school's scheme (if they had one), the enacted curriculum at classroom level, and the state's mandated curriculum. The failure to acknowledge the role of these "somethings" in the production of a learning outcome is a favoured strategy of Newspeakers.

In The Educational Imagination Elliot Eisner distinguished three types of objectives:

Behavioural objectives: predetermined skills, understandings and dispositions deemed as desirable for a pupil to learn.

Problem-solving objectives: skills, understandings and dispositions acquired by a child engaging alone or with others in an act of problem-solving.

Expressive objectives: skills, understandings and dispositions acquired by a child as the result of being exposed to a rich experience, e.g. of some aspect of the natural environment.

I attempted to use all of these as a teacher and teacher educator. Type 2 was a perfect fit for drama-based teaching. Type 3 might involve my taking my Year 9 Northcote College students into Kauri Glen for a sensory awareness experience (consistent with Aotearoa's time-honoured "language experience" tradition for enriching students' language acquisition.)

I have always seen the ability to formulate objectives as the key teacher professional proficiency. It obliges one to articulate what one is on about by focusing on the potential implications of activity design for a child's learning. Objectives can be large-scale, as in the case of unit planning. Or they can focus on something as specific as: "Can use concrete language to communicate a sensory experience."

From 1994 onwards, I observed a number of outcomes of the structure and discourse of the 1994 English Curriculum. Two decades on, I think these still apply. Here are a few of them:

Teachers began letting themselves off the hook since the Curriculum provided a ready-made set of achievement outcomes. If they did produce a lesson or unit plan, it was a simple matter to utilise wording in the document.

Some department began using the Curriculum levels as the basis for rewriting their school schemes, insisting that teachers use the objectives associated with a class's age/stage for their planning. The findings of the Duthie report mentioned above were disregarded. In some obvious ways, the Curriculum's model of progression was a nonsense, suggesting as it did, for example, that mastery of narrative was likely to precede mastery of argument (try telling that to a 2-year-old!) and that critical thinking could wait in the wings until Level 7. To put in bluntly, adhering to the model was a good way of dumbing down students. (My mantra with my pre-service, English teachers at Waikato was: "Teach to Level 8 regardless of the class.")

Construct validity: This is a big theme, so I'll use a simple example here. Construct validity refers to the way in which an assessment task and its accompanying criteria construct what it is that is being assessed. Where this happens in a way that is limited or questionable, then there is a danger that it can colonise a teacher's knowledge in negative ways. An example from the 1994 EC: In the “Close Reading” strand at Level 1, it stated that students should “respond to language and meanings in texts”. I sometimes refer to this as the can-opener theory of reading, where the meaning is somehow contained in the text and the reader has to prise it out. However, the criterion is premised on a construction of reading that is at least contestable if not downright dubious. Why not something like: "make meaning in engaging with texts"?

Of course, contestation relies on the professional knowledge of the profession. Totalitarianism profits from systemic ignorance and the suppression of expertise. When the NCEA was first introduced, teachers were herded into large halls for the purpose of the inculcation of an ideology founded on a separate standards model of credit accumulation. These meetings were called "Jumbo Days", but woe betide anyone who drew attention to the elephant in the room. NCEA Achievement Standards are rife with issues of construct validity.

Returning to 2024, I would draw your attention to Susan Sandretto's recent professorial address entitled "A Case for Future-Facing Literacies"

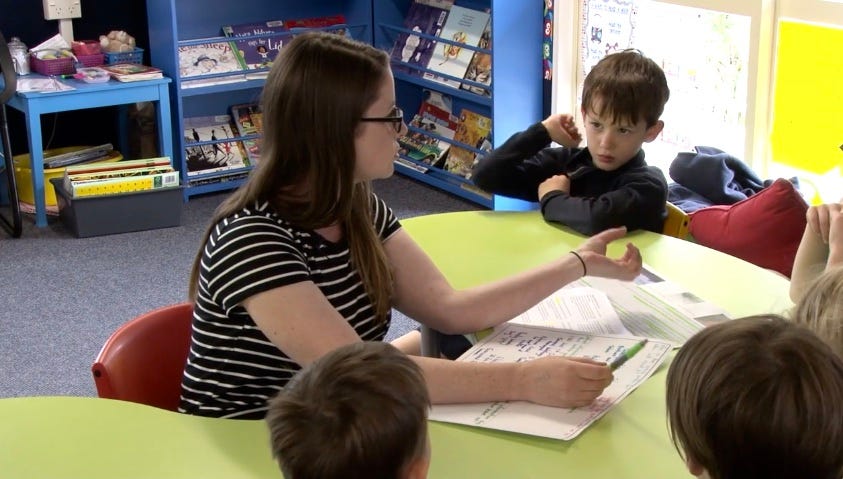

and a lesson undertaken by a teacher with a group of 6-year-olds focused on news story (beginning around 42.44 minutes into the address). Working backwards from what I view, I would identify one the teacher's objectives as something like: "Can identify and explore an author's intention based on textual evidence". (To see more of Hayley’s teaching, click on the link.)

Based on the MAG's rewrite of the pre-2024 curriculum refresh, I can't see this kind of teaching (critical literacy) being encouraged by the kinds of objectives implicit, for example, in their glossary of terms. (For a doctored version of this, go to https://bevanholloway.com/2024/09/12/a-subject-worthy-of-study-enriching-the-rewritten-english-curriculums-glossary/)

In another recent experience, I witnessed a young child reading an iDEAL booklet which appeared designed to enable her to make a connection between the "t" sound and letter "t". The booklet feature a small Sumo wrestler, often observed in school playgrounds in Aotearoa, and there was a lot of hitting occurring. She had mastered each word perfectly, each pronounced with exactly the same intonation in a way that suggested that the content of the storyline, such as it was, was irrelevant to the task. I had a flash back to "Run, Janet run!" I'm sure there was a carefully thought-through learning intention lurking behind this text, but nothing remotely indicative of the broad view of literacies learning that most of us would want for our children.